Case Study: Biomass for a Brickworks

Summary

This case study features the planting of two varieties of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), a fast-growing tree species not normally cultivated in the UK. This pioneering trial is being undertaken on agricultural land owned by H.G. Matthews, a traditional brickmakers[1] located in Buckinghamshire, which burns large quantities of locally sourced wood in boilers and kilns for drying and firing bricks. Prompted by the rising cost of their fuel, concerns over potential future shortages of wood and the eventual expiration of its current Renewable Heat Incentive agreement, the business is investigating whether it can become self-sufficient in fuel. There is also potential for a new revenue stream for H.G. Matthews based on timber sales, since one of the two cultivars of black locust being trialled can yield high quality hardwood.

Background

Established in 1923 in the Chilterns area of Buckinghamshire (north west of London), H.G. Matthews manufactures traditional wood-fired bricks for conservation/restoration and high-end new build markets. In the 1940s, the family started farming arable crops on 260 hectares of land close to the brickworks. More recently, the company diversified into ecological building materials such as manufactured natural blocks called ‘strocks’, containing straw grown on the farm. The company employs 55 people across its brick-making and agricultural businesses.

Bricks are made primarily of clay and sand; prior to firing, the wet, moulded bricks need to be dried. Traditionally they were laid outside to dry in the sun between April and September but since the 1940s H.G. Matthews has dried the bricks indoors in a heated room, enabling year-round production. Heat was initially provided by a coal-fired steam boiler, later modernised to burn oil, with some 30,000 litres of diesel consumed per month for drying the bricks. In 2009, as the diesel boiler was reaching the end of its life, the company replaced it with a 600 kW biomass boiler (motivated by the high prevailing oil price and in anticipation of a growth in demand for low-carbon bricks). The investment proved unsatisfactory (the heat-exchanger failed and the boiler underperformed in terms of heat production), but in 2012 the company was encouraged by the recently introduced Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) to double-down on biomass, this time purchasing four 199 kW boilers at a total cost of approximately £400,000. Under RHI regulations each boiler required a dedicated wood chip storage bunker. To save costs, four redundant 25-tonne grain bins were repurposed to serve as bunkers.

Around 2,000 tonnes per annum of cord wood is sourced primarily from within 25 miles of the farm, the surrounding Chilterns countryside among the most heavily wooded areas of southern England. Approximately two-thirds of this purchased fuel is softwood (e.g. larch, pine) which is chipped and burnt in the biomass boilers. The company hires a chipper every 6 weeks to produce 30 to 40mm diameter chips. Renting a chipper was deemed more economic than purchasing with the outlay on a chipper being as much as £500,000, excluding regular maintenance and insurance, whereas hiring costs just a few thousand pounds each time. The remainder of the purchased fuel is hardwood (e.g. beech, ash), burnt in the kilns used for firing the bricks. This kiln wood is not chipped but mechanically cut into ‘extra-large’ 45 cm logs, then fed manually into the kilns by two people working 12-hour shifts and working 28 fireholes. Batches of 60,000 bricks are fired at a time.

Since 2009, timber costs have risen from approximately £25 per tonne to as much as £90 per tonne (of unchipped cord wood), a trend that may reflect increased demand for biomass energy, compounded by recent restrictions in global timber stocks (resulting from the war in Ukraine). Biomass energy is therefore today only viable for H.G. Matthews thanks to the RHI subsidy. However, the 20-year RHI agreement is due to expire in 2032 with the scheme now closed to new entrants. While it is possible that the low-carbon bricks manufactured by H.G. Matthews may attract a premium by then (economically justifying the continued use of biomass energy), this is by no means certain – nor indeed is future availability of local wood. Therefore, Managing Director Mr Jim Matthews recently began exploring the option of growing their own biomass crop to maintain use of the biomass boilers in the face of rising energy costs and the loss of the RHI subsidy, and to secure a fuel supply.

Introducing black locust

Mr Matthews decided not to grow biomass species typically grown in the UK, such as willow, poplar and Miscanthus, because of his understanding of the demands of the brick kilns. He considered the financial (and energy) costs of drying and storing such crops prior to combustion were likely to outweigh any projected benefits. Instead, Mr Matthews decided to try growing the black locust tree as a promising alternative. He had learned about the species during a Biomass Connect demonstration event at the premises of Biomass Connect partner Bio Global Industries Ltd (BGI), which by chance are located just one kilometre from the brickworks.

Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), sometimes known as ‘false acacia’, is a medium-sized hardwood deciduous nitrogen-fixing tree, native to the Appalachian mountains of the southern United States. Prized for its rapid growth and for the high calorific value and naturally low moisture content of its wood, black locust is today widely planted around the world for both lumber and energy production. As a nitrogen-fixing tree, black locust can also enrich impoverished soils and it was partly for this reason that the species has been widely planted in previously degraded and sandy soils in eastern Europe since the early 1700s (today, 25% of all forests in Hungary are made up of black locust). More information on black locust is available on our black locust crop information page.[2].

Mr Matthews decided to plant two cultivars of black locust (developed by Silvanus Forestry[3] in Hungary), each with a different intended application:

| Black Locust Turbo – for fuel | Black Locust Turbo Obelisk – for agroforestry |

| Black locust Turbo seedlings were planted as an experimental short-rotation biomass crop ready for initial harvesting after two or three years. Mr Matthews plans to use the larger stems and branches of harvested black locust as well as the brash. All of this will be chipped for the biomass boilers. As in the wild, the black locust Turbo cultivar is a multi-stemmed tree and easily coppiced, suggesting its suitability for biomass applications. However, this will be one of the first times the species will be grown and chipped for this purpose (in Eastern Europe the tree is used for firewood logs only). | Black locust Turbo Obelisk saplings were planted as a silvo-arable agroforestry crop, in other words, a single area of land managed to produce both timber and arable crops. In this case, H.G. Matthews intends to interplant wheat and barley in the agroforestry plantation. Black locust roots are proficient nitrogen fixers, providing natural fertilisers to the soil. This will likely start benefiting the arable crops within three or four years, reducing the need for artificial inputs. Black locust Turbo Obelisk has been bred over the last 30 years to produce a single, straight trunk, making this cultivar ideal for timber production. It should be noted, however, that black locust’s performance in the UK is still poorly understood – so the results of Mr Matthews’s trial will be keenly watched. |

When mature, the black locust crowns will be used at the brickworks for biomass burning. The cordwood meanwhile will either be used in H.G. Matthews’s kilns or more likely sold as construction timber to meet a growing demand for locally grown construction materials. The proceeds from these sales could be used to purchase cheaper wood for the kilns. Another marketable product (within 8 to 9 years of planting) is post and rail manufacturing, particularly because of the high tannin content of all black locust wood. This in-built natural preservative provides longevity in microbially active environments, reducing the need for artificial treatments (even with such treatments, traditional post and rails tend not to last more than three or four years in UK soils with a high microbial count).

Environmental conditions for black locust

Black locust grows across a range of climates and soils, and is generally drought-tolerant, though particular conditions are favourable for successful development[4].

- Grows well where mean annual temperatures are over 8°C

- Can grow in regions with as little as 500 mm annual precipitation

- Late and early frosts, as well as low winter temperatures, can be damaging

- Tolerates diverse pH from 3.2 to 8.8

- Tolerates dry and nutrient poor soils, but grows best on deep, nutrient-rich, moist, uncompacted, well-drained light soils (silt loams, sandy loams, or sandy soils)

- Rendzinas, calcium-carbonated soils in the upper horizons, poorly drained and highly compacted (clayey) soils, very dry as well as hydromorphic soils with gley or pseudogley, are not suitable

- The groundwater table should be deeper than 150 cm as nitrogen fixing bacteria of black locust are inhibited by high water table and periods of flooding

Environmental Impact Assessment

Prior to planting, an environmental impact assessment (EIA) was required by Forestry Commission England. This was because the area of Mr Matthews’s farm initially proposed to be planted (approximately 5.9 hectares) exceeded the threshold set out in Forestry Commission guidance on ‘projects likely to have significant effects on the environment’[5] and was sited within an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) (in this case, the Chilterns AONB).

The EIA application required the following:

- A full constraints check for any priority habitat, sensitive soils, designated areas and public access rights.

- Environmental screening for landscape character, erosion and flooding.

- A lifecycle proposal with consideration given to what the future land use intention or ‘end of life’ will be.

- A landscape context plan of the proposed site and local landscape features.

- Detail of management objectives.

- Stakeholder engagement with an accompanying issues log.

- A desk and field survey of the site to establish any vulnerabilities, threats, access issues and utility infrastructure.

- Historic Environment and National Character profile report.

- Evidence of the proposal adhering to UKFS forest design principles.

In October 2023 an environmental consultant was commissioned to carry out the EIA. In the event, different, far smaller pieces of land on the H.G. Matthews farm were planted with black locust (as detailed below). This led to a confirmation in March 2024 that the proposal would not in fact require Forestry Commission consent under the EIA regulations, a decision valid for 5 years. The change of plan occurred after H.G. Matthews was incentivised by a UK Government scheme to use the larger area of land for wildflower meadows instead. The scheme, AB8: Flower-rich margins and plots[6], pays land managers £798 per hectare planted with wildflowers.

Planting

On 11 April 2024 the black locust saplings of both cultivars were delivered as bare roots from Silvanus Forestry, Hungary, and planted the following day. The planting, in an area west of the brickworks, was in relatively small parcels for the purposes of research and development, with the intention to scale up both crops should these initial experimental plantings be successful. Prior to planting, a cover crop of winter wheat had been sown on the land selected for the black locust, to suppress weeds and aerate the soil.

Planting of the two black locust cultivars was undertaken as follows:

Black locust Turbo – for SRC biomass for fuel

Some 4,320 black locust Turbo saplings were planted 0.8 m apart in SW to NE rows following the orientation of the field across 0.72 ha, equating to a density of 6,000 stems per hectare. This relatively dense planting is intended to maximise the biomass for short rotation coppicing. Space was allowed at the end of rows for machinery movement (header racks). Given the need to plant a large number of bare roots as quickly as possible, existing farm machinery – specifically a vintage Danish cable-trenching machine and a Christmas tree-planter – was repurposed to the task of planting. Elsewhere in the Chilterns, a region whose soil is known for a high flint content, a mechanical approach of this type would have been impractical; however, the soil at H.G. Matthews farm is unusually low in flint and the planting was completed in a single day without mishap. The Christmas tree-planter was used for around three-quarters of the saplings, and the trencher for the rest. Although planting with the trencher is slower, it provides a good tilth and friable root bed, which may potentially result in a better quality crop.

Black locust Turbo Obelisk – for agroforestry

Shortly after the black locust Turbo planting, 200 micropropagated saplings of black locust Turbo Obelisk were planted across 0.75 ha in holes hand-dug using a spade to a depth of about 20 cm. The rows were planted in a north-south orientation to allow as much sunlight as possible to the crops between the rows, with 15 m spacings between them. The choice of spacing sought to maximise the number of trees planted in a given area, while enabling access to standard agricultural equipment (e.g. tractors, medium-sized combine-harvesters, etc.). Within the rows the trees were planted at 3 m intervals.

Crop management, monitoring and harvesting

Directly after planting all saplings were cut off to ground level. This practice enables the root system to develop in advance of the stem, providing a robust anchor for the growing crop. New above-ground growth is expected within three months of planting. In autumn, both the biomass and agroforestry crops are monitored for failures, with any gaps filled in with additional root stock.

Mr Matthews intends to manage the two recently planted crops in different ways:

Management of black locust Turbo – for SRC biomass fuel

For protecting the black locust Turbo saplings from wild grazers, a 2 metre-high deer fence was erected in May 2024 around the planted area at a cost of £5,000. Mr Matthews intends to maximise the benefits of the enclosure by also introducing chickens. Initially, due to the legislative hurdles of farming chickens commercially, the eggs from a small flock of perhaps 50 birds will be distributed freely to brickworks employees. The chickens, which offer the additional potential benefits of fertilising the trees through their droppings and controlling invertebrate pests, get introduced to the enclosure when the trees are established after six to eight months. If the biomass experiment proves a success and the black locust Turbo is planted over a wider area, Mr Matthews may switch to selling the eggs commercially.

Weights and height measurements of the biomass crop will be taken after two years to assess survival and viability, and to estimate total biomass. The relative performance of trees planted with the trencher and Christmas tree-planter will also be assessed. At this point, an initial harvesting may be warranted, potentially using an adapted forage harvester, with direct chipping on the field. Should an additional 12 months’ growth be required, harvesting will likely be undertaken using small-scale agroforestry machinery with grabs and blades mounted on a platform. The harvested material will be cut, stacked and then chipped prior to use in the biomass boilers. As noted, a significant benefit of using black locust as a biomass energy source, is its low moisture content at harvest, obviating the need for expensive drying and storage prior to use.

Management of black locust Turbo Obelisk – for agroforestry

Due to the cost, the agroforestry crop was not fenced but instead protected using plastic tree guards which Mr Matthews had on hand. As discussed below, he is considering using biodegradable tree guards for future plantings. When sapling height reaches 1 metre, potentially after 3 or 4 months, a spray-on lanolin treatment can be administered to the leaves to deter deer. The agroforestry crop is then monitored approximately every two weeks to assess the efficacy of these measures in protecting saplings from grazers. A small amount of pruning is needed for the agroforestry crop to ensure a straight trunk, with any small branches removed off once or twice annually. The black locust Turbo Obelisk in the agroforestry planting will be harvested manually using chainsaws.

Challenges

Non-native status and invasiveness potential of black locust

A key challenge with black locust is its reputation as an invasive species. Some experts assert that the risks are exaggerated, arguing that the tree is a pioneer species requiring high light levels and therefore poorly equipped to invade and outcompete native species in mature woodlands with closed canopies. Furthermore, black locust seed germination requires fire exposure. Nevertheless, the non-native status of the black locust was of particular concern to Forestry Commission officials, who pointed to the proximity of the proposed planting site to priority deciduous woodland habitat where biodiversity planting native deciduous woodland is encouraged. Moreover, the Forestry Commission would normally class the proposed planting density of the agroforestry crop of approximately 267 trees of a single species per hectare as ‘woodland’ and therefore requiring their consent (the usual threshold is 100 trees per hectare). In the event, due to the small scale of the planting project, Forestry Commission consent was not required under the EIA regulations. Should Mr Matthews decide to expand his black locust crop, he may propose using a mixture of species to overcome this issue.

Absence of domestic nursery for black locust

Despite black locust being among the world’s most widely planted trees, no nursery source for black locust in the UK currently exists. As a result, anyone wishing to plant black locust in the UK must import: under current phytosanitary regulations, any living plant material sourced from a European Union Member State cannot be delivered to the UK in soil plugs, but rather must be delivered as bare root stock with an extremely limited shelf-life of three days or fewer. Fortunately, the Brickwork’s saplings were shipped and delivered from Hungary within 24 hours.

Lack of EIA consultants

The detailed requirements of the EIA initially required by the Forestry Commission presented a further challenge: finding a consultant sufficiently qualified to address these issues proved to be a struggle, with more than 10 individuals and firms approached before one was eventually commissioned to undertake the work. By the time it was confirmed an EIA was in fact unnecessary and approval granted for the project, the ideal period for tree planting in the UK (typically, October to March) had almost passed. With little time left, Mr Matthews had to move quickly.

Grazing pressures

Another important consideration is the need to protect saplings from grazers. Due to the high sugar content of its shoots and leaves black locust is especially vulnerable to rabbit and deer. Typically, fencing is used, such as in large plantations in Eastern Europe, and this was installed by H.G. Matthews for the black locust Turbo SRC biomass crop. However, fencing off large areas is expensive. Therefore, as noted, reused tree guards were used to protect the black locust Turbo Obelisk agroforestry crop, followed by lanolin treatments. Mr Matthews had considered using biodegradable fence guards. Such tree guards are designed to decompose over time, steadily releasing into the soil nutrients which are required by the growing black locust saplings, while avoiding plastic waste in the landscape. He decided that these were not yet economically viable but may be used in the future should the agroforestry crop be expanded.

Establishment and management costs

H.G. Matthews has entirely self-funded the black locust trial, which to date has cost in the region of £15,500, as detailed in the below table:

| Price/unit | Units | Price | VAT | Price inc. VAT | |

| Turbo Seedlings | £0.76 | 4,350 | £3,306.00 | £661.00 | £3,967.00 |

| Turbo Obelisk | £4.00 | 200 | £800.00 | £160.00 | £960.00 |

| Shipping of seedlings and saplings | £693.02 | 1 | £693.00 | £139.00 | £832.00 |

| Customs Clearance Certificate | £85.00 | 1 | £85.00 | £17.00 | £102.00 |

| EIA consultant costs (indicative)* | £3,000.00 | 1 | £3,000.00 | £600.00 | £3,600.00 |

| Deer fence (Turbo biomass crop) | £5,000.00 | 1 | £5,000.00 | £1,000.00 | £6,000.00 |

| £12,884.00 | £2,577.00 | £15,461.00 |

*In other situations, the EIA consultant costs could have been significantly lower or even not needed at all; however, these are included as they reflect the actual costs paid by H.G. Matthews in this case.

Going forward, Mr Matthews expects to pay annual costs of approximately £1,500 for managing and harvesting the biomass crop, and £1,000 for the agroforestry crop for this experimental planting. There are also estimated opportunity costs, in terms of lost wheat and barley yield from the biomass plot, of about three tonnes per year, worth £500 at current prices, according to Mr. Matthews. For the agroforestry plot, lost arable crop yield is around 0.5 tonnes/year (£80-90 based on 2024 prices ) – however, in later years Mr Matthews expects to recoup some of this given the assumed boost to crop yield from the black locust nitrogen-fixing.

As a novel biomass crop in the UK, the Biomass Connect project will be following the outcomes of this trial with great interest.

References (in order of appearance)

- https://www.hgmatthews.com/

- https://www.biomassconnect.org/biomass-crops/black-locust/

- https://silvanusforestry.com/

- https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/ecology-growth-and-management-of-black-locust-robinia-pseudoacaci

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/environmental-impact-assessments-for-woodland

Latest Technical Articles

Case Study: Biofiltration blocks of Short Rotation Coppice willow used for riparian protection to reduce nutrient run-off into the water environment.

Summary/Abstract

Diffuse agricultural pollution is a major contributor to water quality decline in the UK. Using fast growing woody tree species such as Short Rotation Coppice (SRC) willow can provide a simple and economical solution. This case study features a field trial of willow used for riparian protection to reduce nutrient run-off into the water environment. An experimental trial site was originally established at the Agri-Food and Bioscience Institute (AFBI) Research Farm near Hillsborough, Co. Down, Northern Ireland (54.452264, -6.074844) to investigate the extent of Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorus (P) run-off and drainage from an intensive agricultural livestock farming system. The study covers the set-up of the trial, data comparing P export in the surface run-off under SRC willow and grass, and estimated values of the impact of P removal, as well as potential income from biomass.

Background and Objectives

Given the recent focus on water quality decline (e.g. Lough Neagh & Wye Valley) where diffuse agricultural pollution must shoulder some of the blame[1][2], the opportunity for water quality protection using fast growing woody tree species such as Short Rotation Coppice (SRC) willow is emerging as a potentially viable part of the solution. Point and diffuse sources of pollution are contributing to this water quality decline, however, unlike point source discharges (wastewater and sewage discharge pipes) where the problem can be dealt with in a targeted and structured manner, diffuse pollution is more unquantifiable and variable. Diffuse sources of pollution are also affected significantly by soil type, agricultural activity, weather and to an increasing degree, climate change.

The ability of SRC willow/soil systems or biofiltration blocks to bio-filter wastewater from a variety of sources such as wastewater treatment works, septic tanks, agri-food processing and even leachates from land-fill sites, has already been demonstrated and it is believed that this approach could be used to address diffuse pollution from agricultural land[3]. SRC willow is fast growing, takes up large volumes of water and utilises nutrients, in particular Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorus (P), thereby mitigating run-off of these nutrients into ditches, streams, rivers and lakes. At the same time, the crop is a sustainable source of biomass which could be used for on-farm energy generation, biomass fuel supply or other non-bioenergy uses (e.g. bedding, biopackaging, pulp, phytoceuticals etc).

AFBI has been assessing the effectiveness of SRC willow/soil bio-filtration blocks in reducing the overland flow from agricultural land. As part of the EU funded Interreg VA CatchmentCARE project (https://catchmentcare.eu/), bio-filtration blocks have been set up at the base of a sloping grassland site, to investigate how much nutrient (P) can be intercepted and removed from run-off before it enters the stream at the bottom of the slope. Grassland plots, with and without SRC willow/soil bio-filtration blocks, are being monitored and compared over several years to test whether and to what extent SRC willow biofiltration blocks can protect water quality from the overland flow of nutrients.

Description

The biofiltration field trial at AFBI was constructed on a hill slope site and consists of six hydrologically isolated plots (each 0.2 ha) measuring 143 m x 14 m. Run-off from each isolated plot is collected in a trough at the bottom of the hill and directed to separate v-notch weirs with flow proportional monitoring of surface run-off water (Figure 1). The uphill grass land area is essentially managed as with the rest of the farm whereby slurry is applied in accordance with the N. Ireland Nutrients Action Programme 2019-2022[4].

In 2016 this site was repurposed by planting SRC willow at the foot of three of these plots in order to develop long term evidence on whether targeted SRC willow would function as a biofiltration block and provide riparian protection to reduce the overland run-off of pollution into the receiving stream. All plots have been treated in exactly the same way and had similar P indices ranging between Olsen 2 and 3.

The location of the three experimental plots in the farm landscape can be seen in Figures 2 and 3. Furthermore, the Hillsborough research farm was surveyed using LiDAR (light detection and ranging), with this data being incorporated into a Digital Terrain Model (for soil depth and hydrological conductivity). This reveals the areas of hydrological sensitivity (HSA); the areas at greatest risk of generating overland flow as a result of a rain event. These are the areas that were targeted for willow planting as seen by the yellow outline area in Figure 2 and the same area with growing crop two years later in Figure 3.

Figure 1: Constructed run-off plots with willow and grass biofiltration blocks

Figure 2. LiDAR imaging indicating overland flow risk hence, the targeted area for planting SRC blocks at AFBI Hillsborough (yellow outline). Replicated run-off blocks as per Figure 1 (red outline).

Figure 3. Mature SRC run-off plots and catchment protection plots.

The willows were established according to best practice guidelines[5]. The plots were sprayed (with glyphosate) in April 2016 and planted in May/June the same year and although planted by hand, the spacing and density of planting was kept the same as would be expected from mechanical planting. This is a spacing of 1.5 m between double rows, 0.75 m between the rows in the double rows and the plants were planted 0.45 m from each other within the row. Five double rows were planted giving a buffer strip width of 9.75 m. The willow varieties were chosen from commercial listings and from UK and Swedish breeding programmes to widen the genetic diversity for protection against plant diseases and predation.

The plots were 14 m long x 9.75 m wide. Each block therefore being 0.013 ha in size and containing around 220 willow plants.

On occasions as a result of a rain event, the overland flow is collected by a shallow trench running across the width of each plot as seen in Figure 7. Once triggered the samplers measure the volumetric flow and collect some run-off for lab analysis.

Successes

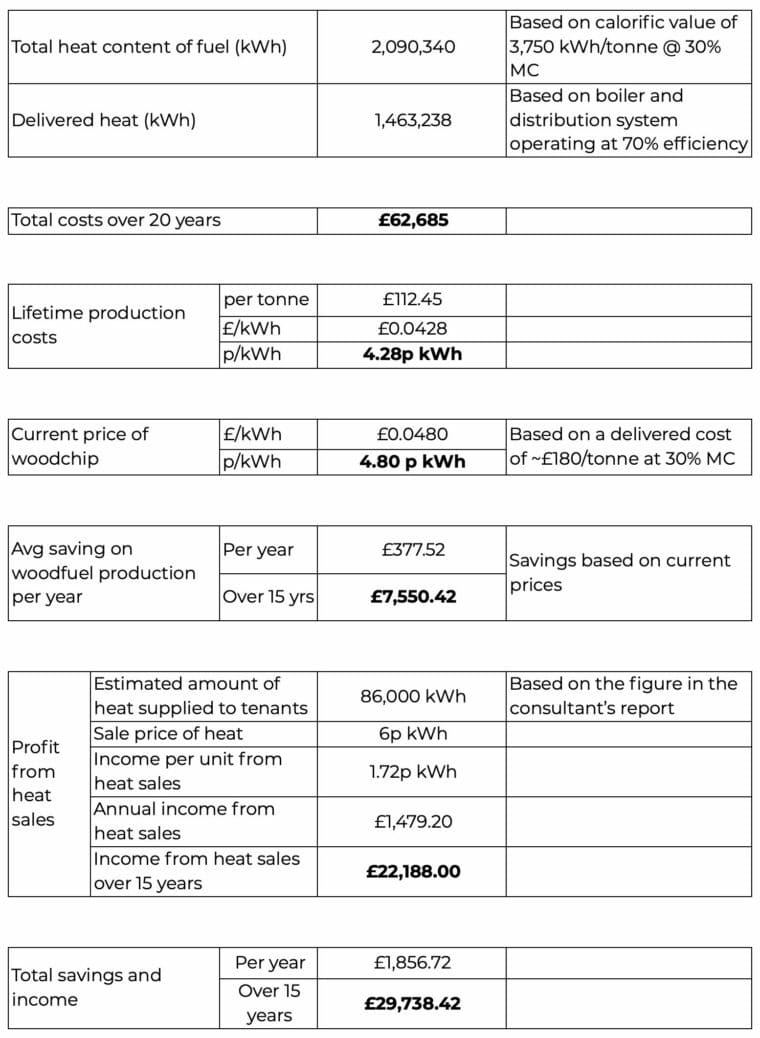

Early indications suggest that the willow blocks are reducing the run-off of P. Figure 5 indicates a lower average P load accumulation from samples below the willow blocks (blue line) compared to grass controls (red line). Over the years the data indicates a reduction in Total P load run-off of between 20% and 37% with an average reduction of 35%. Furthermore, soil moisture content is consistently lower and hydrological conductivity (measured using Saturo Monitoring) is consistently higher in the willow blocks than the grass plots, revealing likely reasons for these reductions in nutrient run-off.

Figure 5. Preliminary results Indicate increasing differences in average P export between grass (red line) and SRC plots (blue line).

These results have been consistent over a recent 6-year period and indicate that the targeted placement of SRC willow buffer strips does indeed seem to be reducing the diffuse run-off of P from the agricultural field.

Challenges and Practical Considerations

Although the replicated platform consists of 3 replications of grass and 3 of willow (treatment), there are challenges given the age and integrity of the site. However, the data does indicate a strong effect on reducing P run-off. The construction of a comparative experiment using real world buffer biofiltration plantations is difficult given the infinite variability from site to site.

The plantation targeted using LiDAR and established as in Figure 2 (yellow outline) and growing well in Figure 3 is naturally unique. In order to detect a direct effect of this, it would be necessary to collect long-term water quality data, along with flow volumes, pre-establishment and again long-term data afterwards. Long-term water quality data has been collected at the AFBI Hillsborough Farm and a number of Hydrologically Connected Areas (HCA) have been targeted and planted in this way. There is potential to record some improvements in water quality as a result. However, it is more difficult to decide whether improvements are as a direct result of the bio-filtration or combined to include other actions such as different livestock stocking and management, improved slurry management, manure and dirty water management or simply variable weather patterns, where climate change will almost certainly be playing a role.

The replicated trial was an experiment so all planting and harvesting operations were carried out by hand. Planting was done in April 2016 and the SRC plots were harvested manually using chainsaws and brushcutters every three years between the months of November and March. So far harvesting was completed in 2020 and 2023. The next harvest will be carried out in 2026.

If this type of application is to become a mainstream activity on farms, machinery needs to be developed that can plant and harvest in a low cost, efficient and low impact manner given the likelihood of wetter and therefore less easily managed areas of the farm.

Costs and Benefits

Valuing SRC willow in an Agricultural Environment

If we are to accept that agricultural production systems must no longer focus solely on production efficiency but embrace and adopt increasing measures of environmental sustainability with respect to water, air and soil quality as well as biodiversity and soil carbon net gains, then the targeted planting of SRC willow biofiltration blocks to protect water quality would seem to be a logical and sensible approach. However, understandably, it is clear that farmers and land managers can be reluctant to dedicate areas of farmland from the primary agricultural production focus into less profitable uses.

A further study[6] therefore set out to investigate the economic and environmental return of diversifying into SRC willow in an intensive agricultural landscape. This study utilised the buffered sub-catchment at AFBI Hillsborough (Figure 3) along with real world data to develop a Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) overview of costs.

Although it is possible that this diversification option can be profitable on its own, dependent on the availability of certain supply chains and harvesting strategies, it generally represents a loss when integrated into a typical dairy farm. However, when a monetised value of certain ecosystem services (nutrient removal) is incorporated, there was minimal impact on the economic return on the dairy land.

Valuing Phosphorus removal from the water environment

The Farmscoper / ADAS estimated values for nitrate, phosphorus and sediment originally based on Chadwick et al (2006) for DEFRA research and expressed in 2021 prices in version 5 of the Farmscoper tool[7] estimate the economic damage from water pollutants across a range of ecosystem goods and services (e.g. drinking water quality, fishing, bathing water quality and eutrophication) and isolate the contribution of agriculture. Based on this the annual value of reducing a kilogram of phosphorus in water from agricultural sources is £39.76.

An approximation for this trial therefore would be:

| Average Total P reduction between 2016 and 2021 from the 14m x 9.75m SRC willow plot (0.014ha) | 54g |

| Average Total P reduction per year (= 54/5) | 10.8g/y |

| Average Total P reduction per ha per year | 815g/ha/y |

| Average Social Value of P removal of SRC willow | £32.40/ha/y |

SRC production costs, yield potential and uses

As the small trial plots are planted and harvested manually it is difficult to estimate the economics of this venture. However, another Biomass Connect case study (SRC Willow – self supply and use in a farm-scale community heating scheme[9]) provides an indication of the costs involved.

If standard yields are assumed*, then these three SRC plots should be capable of producing circa 1.7 tonnes of boiler ready fuel from every 3-year harvest. This is obviously a very small amount of biomass. The farm in the case study referred to above requires 60 tonnes of woodfuel per year and on average produces one third of their requirement from SRC self-supply. To produce that amount of SRC woodchip would require a total area of SRC buffer strips of 1.4 hectares across the farm.

The size and small-scale nature of SRC buffer strip cultivations is possibly better suited to agroforestry than energy production. Willow can provide a useful fodder addition to the diets of livestock and zoo animals. (For more information see the Chester Zoo case study[10]). The rods would need to be harvested in leaf and moved to a less sensitive area where the animals are located. Animals should not be allowed to graze the SRC in situ as their faeces would add to the nutrient load and defeat the purpose of the buffer strip.

Lessons Learnt and Recommendations for Future Projects

This is a research project which set out to try to demonstrate and quantify any water quality benefits of SRC willow biofiltration blocks targeted within the agricultural landscape for riparian protection. The run-off platform has been in operation, for varying environmental applications, since the late 1980s and as such, requires significant and on-going maintenance and management. Automated samplers also require continual maintenance and management from which samples need to be collected and flow data downloaded at regular intervals. The research platform is therefore relatively cost and labour intensive while the infrastructure, due to age, can give rise to some intrinsic failure.

Although, the science would require further temporal data to refine the effectiveness of this type of environmental intervention, the results do seem to indicate that a targeted landscape intervention of SRC biofiltration blocks / buffer strips within catchments that are sensitive to excess P loadings, could contribute to mitigating P run-off. A scheme in which replicated, commercial scale plots, targeted within a specific catchment with regular monitoring would seem an obvious next step.

Figure 7. Chris Johnston of AFBI talking to Jeanette Whitaker of UKCEH (who is leading the Biomass Connect project) in November 2023. The SRC plot has 2-year-old stems on 6-year-old stools. Notice the shallow trench to collect overland flow after a rain event (just in front of Chris’s feet).

References (in order of appearance)

- https://www.agendani.com/lough-neagh-an-ecological-catastrophe/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/30/river-wye-has-health-status-downgraded-by-natural-england-after-wildlife-assessment

- https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/5bbeed749d4e46f28b12c0f2367911b1

- https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/articles/nutrients-action-programme

- https://envirocrops.com/resource/short-rotation-coppice-willow-best-practice-guidelines

- https://pureadmin.qub.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/410955897/1_s2.0_S2352550923000131_main.pdf

- https://adas.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/FARMSCOPER5_Description.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652623020942

- https://www.biomassconnect.org/technical-articles/case-study-src-willow-self-supply-and-use-in-a-farm-scale-community-heating-scheme/

- https://www.biomassconnect.org/news/new-media/willow-at-chester-zoo/

•Willow is harvested green with a moisture content of 55%. The average yield of a hectare is around 55 tonnes of green biomass. This is equivalent to ca. 10 dry tonnes per year or 14 boiler ready tonnes per year.

Contact Details and/or Links to Further Information:

Chris Johnston

Agri-food and Biosciences Institute

Agri-Environmental Technologies

Environment and Marine Sciences Division

Large Park

Hillsborough

N. Ireland

BT26 6DR

(+44 (0) 28 92 681540)

http://www.linkedin.com/pub/chris-johnston/4/9b6/984

[email protected]

Further information can be found on the Biomass Connect website or by contacting the Biomass Connect Project Office and referencing Case Study 2.4-2.

Latest Technical Articles

Case Study: Grower Walter Simon’s Miscanthus Success Story

Summary

Walter Simon, a farmer in south Pembrokeshire, has successfully grown Miscanthus on 4 ha of ALC grade 3b land for the last 17 years. The Miscanthus was initially intended for biomass fuel but is now used as bedding for his neighbour’s dairy cows. For the dairy farmer this switch to a Miscanthus base-layer proved superior for cow welfare and environmental sustainability, offering a viable alternative to wood chip and straw. Despite challenges with yield, potentially due to soil compaction, the crop’s economic viability remains strong with a gross margin comparison favouring Miscanthus over traditional crops like winter barley on similar quality land.

Background

As part of a 140-ha mixed farming enterprise in south Pembrokeshire, Walter Simon has been growing 4 ha of Miscanthus for the last 17 years.

The parcel of land that Walter chose for the crop was unsuitable for arable and root cropping and was in permanent pasture. The soil is a slightly acid loam and although it is generally free draining, the bottom section of this particular field is poorly drained.

Walter was encouraged to plant Miscanthus after being contacted by the Pembrokeshire Machinery Ring in 2007 as part of a plan to supply the newly established Bluestone holiday resort, where it was to be used in their biomass heating plant for the leisure facilities.

- Location

- Soilscape Map

Navigating the harvest

Walter initially faced challenges with harvesting. To supply bales for Bluestone, the crop was first mown, and then left to dry for several weeks before baling. This proved challenging as it required a weather-dependent drying period during February and March and doubled farm traffic on the fields during some of the wettest months, raising concerns for Walter over soil damage.

After some informal discussions with his neighbour, Chris James, the pair came up with a transformative solution. Chris, a spring calving dairy farmer, sought an alternative bedding material for his outdoor corrals (a hard-core pad with drainage for out-wintering cows) due to concerns with woodchip sourcing and environmental impact.

By working together, Walter and Chris changed their farming practices by repurposing Walter’s Miscanthus crop as bedding material for Chris’s dairy cows.

Harvesting now takes place in a single pass during a dry weather spell in Jan/Feb, using a standard Kemper type maize header and forage harvester. This makes use of a local contractor at a time when forage harvest work is quiet. It also coincides with Chris’s need for bedding during his calving period.

This harvest system helps to minimize soil compaction by reducing the amount of travel on the field, but still occurs after the crop has senesced (died back) and most of the leaves and surrounding stem sheath has been shed.

Walter understands the importance of waiting for senescence. Leaves and leaf sheaths are generally wetter components of the biomass that are lost during senescence, helping ensure a drier harvest. They also contain higher levels of nutrients than stem material, meaning that the yield quality1 of the harvested biomass is improved by their loss and the nutrients they contain are returned to the soil when they remain on the ground, thus promoting sustainability. The shed leaves and leaf sheaths also provide organic matter input for the soil, even equivalent to those provided by FYM2.

- Leaf material left at the base of the stubble following forage harvesting, important for biomass quality and sustainability.

- Leaf material left at the base of the stubble following forage harvesting, important for biomass quality and sustainability.

A Sustainable Cycle: From Miscanthus Field to corral to grasslands.

During harvest, the crop is chopped and blown straight into trailers to be hauled the approximately 7 miles to the dairy farm where it is tipped straight onto an outdoor pad. The bedding is then spread and compacted to a depth of 20-30 cm to allow the dissipation of dung and urine. Surplus Miscanthus is tipped on to a concrete pad close by ready to use as a top up during the calving period.

According to Chris James’s long-term observations, the Miscanthus chip in outdoor corrals performs well on all counts, proving favourable to the wood chip alternatives. The outdoor area under the pad is very well drained into the slurry store, stopping the build-up of moisture. The Miscanthus is structurally strong and sufficiently inert to last the nine-week calving period, but Chris does replace or top-up in the high traffic areas and during higher rainfall periods.

After calving, the material is left in place over the summer to wick rainfall and help reduce water going into the slurry pit. It is then spread onto ground that is to be ploughed and reseeded for grassland. Chris says that because it is chopped, it spreads easily and breaks down well, unlike wood chips.

Cow Welfare

Chris states that, with regards to welfare, comfort, and lameness, Miscanthus bedding is brilliant if the management is correct. The pad is stocked to allow 10 sq m per cow, accommodating approximately 70 cows at any one time. “When given a choice [between Miscanthus bedding and cubicles], the Miscanthus pad is always the cow’s first choice”.

At calving the cows can lie flat and then recover comfortably post calving when they are at their most vulnerable.

Chris states that Miscanthus doesn’t seem to be the fertile breeding ground for pathogens that straw beds are. In the past, environmental mastitis had been a problem with the outdoor cubicles, but there appear to be no issues with the pads with Miscanthus.

Several studies have shown that Miscanthus is comparable to other bedding material for dairy cows in terms of its physical3 and biological4 properties, and it can help to reduce costs5 because farmers can grow it themselves, thus building self-sufficiency.

- Chopped Miscanthus material in the corral

Crop yield

As with all farm enterprises the ability to measure, monitor, and manage are key principles to assess economic viability. The Miscanthus crop at West Orielton farm was planted in the spring of 2007 and since the first harvest in 2009 Walter has recorded the yields. Fresh weight harvest data shown in the chart below indicate a 16-year yield average of approximately 22 t/ha (see note below on yields and moisture content).

Walter wonders now whether crop yield may be declining, and if this may be due to damage caused to the rhizome mat and soil compaction when conditions are wet at harvest, or if the mature crop has naturally reached a plateau in yield6.

Miscanthus has a long growing period compared to that of a cereal crop, this means that short-lived variations in the season, such as low or high rainfall, will have comparatively less effect on annual yield. However, prolonged spells of adverse weather (e.g. drought and flooding, such as have been experienced in the UK for several years) will affect yield.

- Field damage can be seen in the wetter part of the field (left) compared to the drier areas. This damage may be negatively affecting yield.

It is therefore unclear at this stage whether remediation or a better growing season is needed to try and restore Walter’s Miscanthus crop yield levels, or whether the crop has reached a mature yield plateau.

The dramatic increase in yield seen between harvests in 2011 and 2012 may have been partly due to crop maturity but also to the change in harvest method: from 2009 to 2011 mowing and baling took place in Feb/March when some drying will have taken place, however the forage harvester method (post 2011) is conducted late Jan/early Feb with the crop likely harvested at a higher moisture content. This slightly earlier harvest may also result in more stem biomass being retained, as upper stem parts can break off during harsher winter weather.

Walter has occasionally applied slurry and compound fertiliser, but none recently, and he felt these applications appeared to have little benefit. He also noted that there had been no significant ingress of weeds or noticeable pests requiring chemical control.

The economic viability of Miscanthus

The gross margin below is calculated based on the harvest from the 2023 growing season (harvested 2024) with a fresh weight yield of 82 tonnes in total from the 4-ha site, selling for £45/tonne, and costing around £700 to harvest and deliver to the dairy site. A gross margin of £748/ha/yr compares to a Welsh winter barley gross margin of £730/ha (FBS Farm Business Benchmarking).

As barley is usually grown on better quality land, the Miscanthus compares favourably when using poorer quality land (Agricultural Land Classification 3b), especially areas where use is restricted by impeded drainage.

Walters’ Gross margin

| Enterprise output | Harvest total | Per ha |

| Miscanthus | £3,690 | £923 |

| Enterprise cost | ||

| Harvest and haulage | £700 | £175 |

| Gross margin | £2,990 | £748 |

Chris’s Comparison of Miscanthus and wood chip as bedding for outdoor corals

| Material | Price / tonne |

| Miscanthus | £45 including delivery |

| Softwood chip | £55 plus delivery (price ex Ceredigion sawmill) |

*Prices are not including VAT

It is also important to consider time invested in crop management: Walter states that he spends no more than 4 hours a year with the crop.

Establishment costs 2024

Based on figures from the two main providers of planting stock in the UK, rhizome supply and planter hire costs range from £2,100 – £2,500 per ha, which will vary depending on location and total scale of the area planted. After care of the crop for the first year is important for good establishment. This cost is approximately £138/ha for the first two years.

Labour for planting is usually supplied by the management of the site to be planted. Land preparation is additional.

Going Forward

Looking ahead, Walter is keen to find out about some of the wider environmental impacts of Miscanthus cultivation and is looking forward to getting results from soil sampling conducted as part of a project called Perennial Biomass Crops for Greenhouse Gas Removal (PBC4GGR). The soil samples will help identify the potential of perennial biomass crops, such as Miscanthus, for their contribution to building soil organic carbon content.

Walter also continues to explore avenues for optimisation by considering factors potentially contributing to yield reduction.

Walter concludes that Miscanthus is a great opportunity for people in Wales as the kit to harvest is readily available locally, it is simple to grow and store, and it is cheaper and more sustainable than haulage of straw from England.

Further information regarding technical aspects of Miscanthus agronomy and its suitability for bedding can be found at biomassconnect.org, with best practice guidelines on growing Miscanthus and a cost calculator tool available using a web app such as www.envirocrops.com.

References (in order of appearance)

- Jensen, E., Robson, P., Farrar, K., Thomas Jones, S., Clifton-Brown, J., Payne, R. and Donnison, I. (2016). Towards Miscanthus combustion quality improvement: the role of flowering and senescence. GCB Bioenergy, 9(5), pp.891–908. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12391.

- Beuch, S., Boelcke, B. and Belau, L. (2000). Effect of the Organic Residues of Miscanthus x giganteus on the Soil Organic Matter Level of Arable Soils. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 184(2), pp.111–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-037x.2000.00367.x.

- Ferreira, P., Rossi, G., Conti, L., Araújo, G., Leso, L. and Barbari, M. (2020). Physical Properties of Miscanthus Grass and Wheat Straw as Bedding Materials for Dairy Cattle. Lecture notes in civil engineering, pp.239–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39299-4_27.

- Ferraz, P.F.P., Ferraz, G.A. e S., Leso, L., Klopčič, M., Barbari, M. and Rossi, G. (2020). Properties of conventional and alternative bedding materials for dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science, 103(9), pp.8661–8674. doi:https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-18318.

- Van Weyenberg, S., Ulens, T., De Reu, K., Zwertvaegher, I., Demeyer, P. and Pluy, L. (2015) Feasibility of Miscanthus as alternative bedding for dairy cows. Veterinarni Medicina, 60,(3): 121–132. doi: 10.17221/8059-VETMED

- Shepherd, A., Clifton‐Brown, J., Kam, J., Buckby, S. and Hastings, A. (2020). Commercial experience with miscanthus crops: Establishment, yields and environmental observations. GCB Bioenergy, 12(7), pp.510–523. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12690.

Latest Technical Articles

Case Study: SRC Willow – self supply and use in a farm-scale community heating scheme

Abstract

This case study features a successful farm-scale community heating scheme using short rotation coppice (SRC) willow as a fuel source. The project has been cost-effective and provided a range of benefits, including energy self-sufficiency, reduced carbon emissions, and potential biodiversity enhancements1.

The study examines the challenges faced in establishing and managing the SRC willow plantation, including the need for hard standing space to store and dry rods prior to chipping, the capacity of the fuel store, and the access to wetter areas of the plantation.

Also explored is the harvesting and chipping process, and the issues that have arisen with the biomass heating system.

Overall, the case study demonstrates that SRC willow can be a viable and sustainable energy source for farms and rural communities.

SRC Willow – Self Supply and use in a farm-scale community heating scheme

Background

Umberleigh Barton Farm is a working mixed farm situated in North Devon, belonging to the Andrew family. The Andrew’s have installed a 130-kilowatt (kW) biomass boiler to supply space and water heating to their farm buildings and six residential properties on site, four of which are rented out to tenants.

The 130-kW biomass boiler requires around 60 tonnes of wood chips per year. This is sourced from local woodfuel providers and from 3.95 hectares of short rotation coppice (SRC) willow planted by Mr. Andrews in 2015. At full capacity the SRC willow plantation could supply 100 % of the wood chip needed to run the boiler.

Planting and Harvesting

The decision-making process involved in the selection of SRC as a crop and installation of the boiler is explained in the earlier case study. The most important elements were the desire to achieve self-sufficiency and “insulate” the Andrew family against potential future woodfuel price rises.

The SRC plantation was established 18 months after the boiler was installed. The intention was to hand plant the willow but ultimately Mr Andrew decided to pay to get a specialist contractor (Rickerby Estates based in Cumbria) to plant it using the Step Planter. The additional cost of planting (due to the distance that the contractor had to transport labour and machinery) was offset by the decision to not install rabbit fencing.

Specialised harvesting machinery is not available locally, so the decision was made to plan for manual harvesting with chainsaws and manual onsite processing into woodchips using a static chipper.

The aim was for one quarter of the crop (~1 ha) to be harvested every year to provide a supply of home-grown material to supplement purchased woodchip. Although this involves manual labour and additional handling, the cost of SRC woodfuel is significantly lower in price than purchased woodchip.

As the crop was to be harvested manually it was decided to use wider spacings between the willow rows (2m between rows rather than the normal 1.5m). This gave the plantation a stocking rate of 10,000 per hectare (compared to the commercial standard of ~15,000 per hectare). Mr Andrew followed best practice advice that was available at the time and cut back the establishment year growth in order to promote coppicing. More recent practice is to leave the crop intact and harvest the crop in its third year.

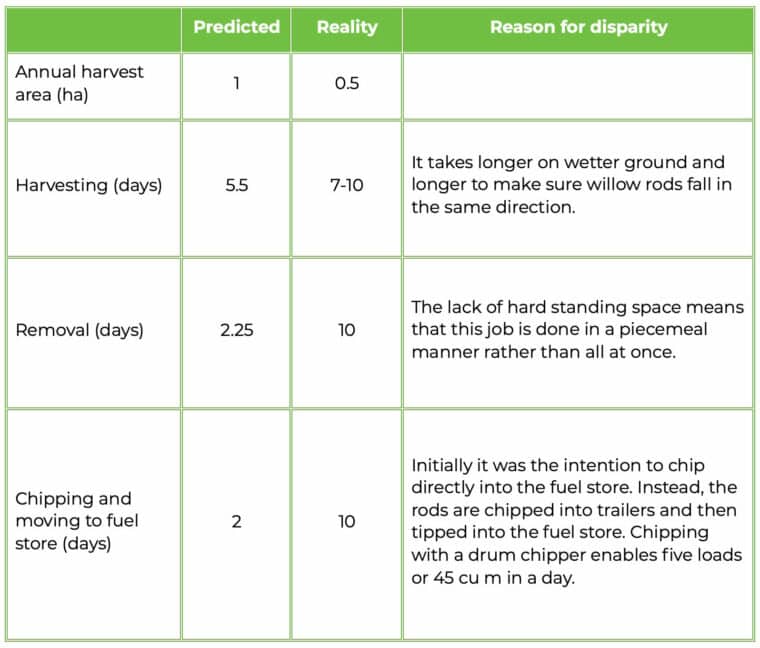

The first harvest was taken in Jan/Feb 2019 (three-year shoots on four-year root stocks = S3R4). The planned harvest regime was adjusted each year based on circumstances, and has resulted in a lower area being harvested than planned and longer rotation periods, with the area harvested each year as follows:

- Jan/Feb 2019: 0.50 hectares (S3R4)

- Jan/Feb 2020: 0.22 hectares (S4R5)

- Jan/Feb 2021: no harvest due to an issue with the chipper (see Challenges)

- Jan/Feb 2022: 0.37 hectares (S6R7)

- Jan/Feb 2023: 0.69 hectares (S7R8)

Successes

The project has been an out and out success. A delay in planting caused by a hold up in the award of the Energy Crops Scheme grant allowed Mr Andrew more time to get the land clear of weed competition. In addition, the machine planting was very successful with only a few misses. Both enabled the crop to get away quickly and achieve canopy closure. In addition, the strong establishment year growth and cut back enabled excellent coppicing, which further suppressed weed competition and provided the best foundations for a high yielding crop.

Mr Andrew was also one of the first people to commercially plant into his mix the variety ‘Endurance’ which was released onto the market in 20152. This variety has consistently been the highest performing variety in yield trials in the West of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It is particularly suited to slightly wider spacings and longer rotations. Five varieties were planted (Endeavour, Endurance, Resolution, Terra Nova and Tordis).

Analysis has indicated that Endurance and Endeavour have superior woodfuel qualities to other varieties including: lower moisture content at harvest, higher lignin content and higher bulk density . During the visit a sample of the wood chip was taken, and the bulk density was found to be 242 kg/m3.

The aim is to harvest the crop in Jan/Feb each year. At this point the willow is dormant so there is no leaf contamination. Wood chips contaminated with leaves tends to be higher in chlorine which can cause corrosion of the boiler’s combustion unit and so this issue is avoided. The excellent yield and longer growing cycle (5 year as opposed to typical 3-year rotation) has meant that the woodchip produced has a much lower bark to wood ratio than typical SRC chip, and the woodfuel produces a lower ash content than would be expected (normally this is 2% but it is estimated that this is reduced by around 25%). Mr Andrew removes a three-quarter full wheelbarrow of ash every fortnight in winter.

So far, there have been no issues with the operation of the boiler. One batch of willow fuel was a little wetter than normal and this resulted in clinker (where ash fused into a hard crystalline deposit), but this was the only thing to report. Mr Andrew has the boiler serviced twice a year which keeps it in very good condition.

The low-cost nature of the venture (see Costs and Benefits section) has enabled Mr. Andrew to maintain the cost of heat supplied to his tenants at 6p/kWh. This is the same as was charged back in 2015.

By contrast at the time of writing (September 2023) the average price of natural gas in the UK is 8p/kWh (and during the Cost-of-Living Crisis from winter 2022 to spring 2023 it was much higher at over 14p/kWh).

Mr Andrew also feels there are additional biodiversity benefits. For instance, willow catkins provide pollinators with nectar and pollen in late winter and early spring; Mr Andrew has permitted a local beekeeper to place several hives around the willow plantation.

In addition, numerous bird species were seen in and around the crop during the case study visit. These included the amber listed Grey Wagtail and Wren, as well as green listed Pied Wagtail, Long Tailed Tit, Blue Tit, Chiff Chaff, Robin and Blackbird. A planned ornithologist’s visit later in the year will explore the role of the SRC in attracting these and other species.

Challenges

The biggest challenge has been the lack of hard standing space to store and dry rods prior to chipping. Mr Andrew created a hard-core pad (~350 square metres) before the SRC was planted but this is not sufficient space and has limited the amount that can be harvested in any one year.

In addition, the capacity of the fuel store means that the rods can only be chipped sequentially. The barn can only handle five trailer loads at a time. The farm uses a telehandler for both the chipping operation (a grab) and for pushing the tipped woodchip into the fuel hopper (a bucket). Replacing one attachment with the other adds time to the processing procedure.

Some parts of willow plantation are in wetter areas than others. These are not so easy to access and further away from the area used for rod storage. So far, this part of the plantation has not been harvested.

As the mature willow is over 8m tall it is important to harvest on a wind free day. This assists the chainsaw operative to orientate the willow to fall in a consistent direction which subsequently allows the telehandler to efficiently grab the willow. The harvesting job is done over a period of weeks to ensure that it doesn’t become boring or lead to repetitive back strain for the operative.

The estimated times required to harvest the SRC, remove the rods to the storage area and then do the chipping are all longer than was predicted (see Table 1). This is a result of the complexity of the harvesting and manoeuvrability of the willow, the space constraints and the need to change attachments to the telehandler.

The chipping process is carried out in September. As willow rods dry quickly it was found that chipping during the summer months led to drier, dustier chips. A slither breaker in the chipper prevents any oversized material causing blockages in the boiler auger system.

No SRC was harvested in 2021. This was due to a problem with the chipper which was causing slithered chips. Covid restrictions meant that the chipper could not be serviced. Once serviced it was returned to correct working order and harvesting was resumed the following year.

The biomass heating system had an issue that was unrelated to the willow fuel. The heat distribution pump failed, and a replacement had to be sourced from Germany. It took 48 hours to arrive, so the family and their tenants were without hot water for three days. Even though Mr Andrew had chosen to retain an oil back up boiler this was no use without the distribution pump. As a result of this the family have now added a back-up pump costing £4,000.

Cost and benefits

The total SRC willow establishment costs were £9,303 (£2,355 per hectare). However, at the time of planting Mr Andrew received a 50% grant from the Energy Crops Scheme (it should be noted that this scheme is no longer active).

The establishment costs were broken down as follows:

Willow rods including haulage £3,327 (£842/ha)

Planting £3,448 (£873/ha)

Ploughing £213 (£54/ha)

Sub soiling £200 (£51/ha)

Power harrowing £213 (£54/ha)

Rolling £60 (£15/ha)

Sprays and spraying £1,092 (£276/ha)

Consultant’s fees £750 (£190/ha)

Total establishment costs £9,303 (£2,355/ha)

The labour costs for harvesting and processing are £82.50 per day3. So, for 30 days a year this is equal to £2,475.

Mr Andrew’s consultant provided him with a case study of the Danish TP chipper range being used for chipping dried SRC rods. Based on this information, Mr Andrew applied for a 40% grant from the Farming and Forestry Improvement Scheme in 2015. A TP230 chipper was purchased for £13,350, of which £5,340 was paid for with the grant. The net cost of the chipper was therefore £8,010.

Mr Andrew has not kept a record of the amount of willow chip produced. However, the inability of the farm to use the chipper in 2021 enabled a comparison of the amount of woodchip purchased in a year when there was no self-supply.

In 2020 the farm purchased £6,492 of chip equivalent to 168 cubic metres and in 2021 the farm purchased £10,500 of chip equivalent to 264 cubic metres. It is therefore estimated that in a typical year the willow produced on farm would contribute 96 cu m to the total (~ 36%). 96 cu m of willow chip is approximately 21.6 tonnes.

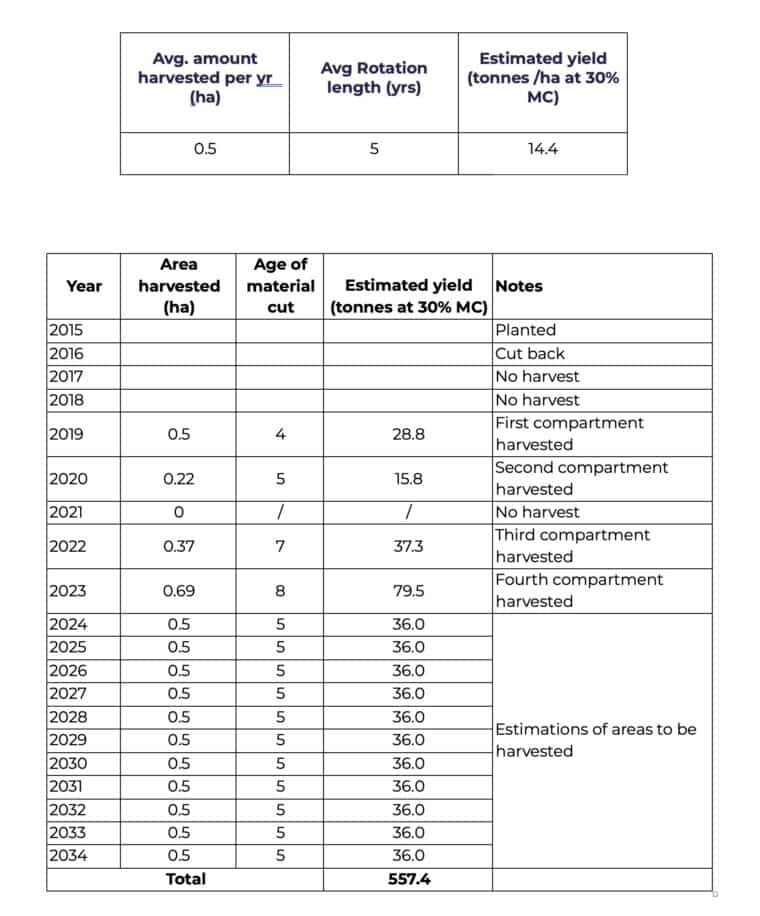

The total SRC woodfuel production costs over a 20-year period (assuming 15 harvests) would be:

Establishment costs (minus grant) £4,650

Harvesting and chipping costs £37,125

Chipper cost (minus grant) £8,010

Lost income from farmland £100 per hectare per year £7,9004

Sundry costs e.g. chipper servicing and replacement parts £5,000

Total costs over 20 years £62,685

Forward projection – if the farm harvests an average of 0.5 hectares per year and keeps to a rotation length of 5 years between harvests and achieves similar yields to those already produced (14.4 tonnes per hectare per year at 30% moisture content), then the plantation will ultimately produce 557 tonnes of boiler ready fuel over a 20-year period.

This would mean that the fuel could be produced for £112 per tonne. Based on the boiler and distribution system operating at an efficiency of 70% the delivered cost of heating is 4.28 pence per kWh.

The cost of purchased woodfuel has steadily increased from £38.50 per cu m in 2020 to £40.50 per cu m in 2023. The current price is equivalent to £180 per tonne or 4.80 pence per kWh.

If the Andrew family farm avoids purchasing 557 tonnes of woodfuel then they would save £7,550 (or £378 per year) based on current prices, once all the costs associated with establishing and managing the SRC have been deducted. However, with the likely rise in demand for woodfuel, this differential could increase further leading to even greater savings.

Furthermore, there is profit from selling heat to tenants. Based on the sale price of 6p/kWh this brings in an additional income of £1,479 per year. As a result, the net revenue benefit over the lifetime of the SRC plantation is likely to be around £30,000 or £1,850 per year5.

Lessons Learnt and Recommendations

This project is an exemplar in that Mr Andrew has from the outset made considered decisions, followed best practice, used quality plant material and engaged well respected and experienced consultants and contractors. He has made good use of grant schemes and has learnt a considerable amount about the practicalities of SRC production from the experience. The most important aspect is the acceptance of the current limitations of his woodfuel handling facilities and the management of the crop, so it provides a significant proportion of the farm’s fuel without becoming overly burdensome.

Mr Andrew is aware that the amount of handling involved could be improved by the addition of a covered outdoor woodchip bunker. This will be considered in the future but at the moment the farm business is focusing on other priorities.

1 This is an update on a previous case study produced in 2015 as part of the EU funded Rokwood project.

2 Willow variety guide: https://www.crops4energy.co.uk/willow-varietal-identification-guide/

3 In the weeks following the case study visit Mr Andrew conducted a trial with a tree shear and was pleased with the way this went. He believes that this will radically speed up and reduce the cost of the harvesting activities, particularly in the wetter areas that so far haven’t been harvested. The cost to rent the tree shear is £40/hr for the machine and the operative.

4 The area planted was very rough grazing and in some years the income would have been nil. The financial loss is assumed to be quite low as SRC also continued to be an eligible crop under BPS.

5 See Appendix for yield calculations.

Latest Technical Articles

Case Study: Producing Animal Bedding from Miscanthus

BACKGROUND

Burlerrow Farm is a 303-hectare mixed farm based in Bodmin, Cornwall. It is run by James Mutton who has been growing miscanthus since 2002. Initially, the crop was used to produce miscanthus rhizomes, but since 2009 they have been producing premium equine and animal bedding. In 2022, the farm business processed over 4,000 tonnes of miscanthus for this purpose. During the last decade Burlerrow Farm has diversified into new markets and now produce miscanthus bedding products (Burlybed), heating briquettes (Burlyburn), and forage products (Burlybale) based on grass, hay or haylage.

Burlybed Products

Products are sold through 100 retailers across the south of England and Wales with the furthest north in Worcestershire and east to Bedfordshire, Essex and Kent.

The farm has agreements in place with 20 miscanthus growers. Eleven of these are based in Cornwall and Devon with Burlerrow Farm contracted to manage the crop. A further nine growers are in Herefordshire, Berkshire, and Somerset. In these cases, the grower manages the crop and sells the bales to Burlerrow Farm.

The Burlerrow Farm premises are heated with an Eta Hack 90 kW biomass boiler fuelled with miscanthus chips. The farm also supplies a separate family-owned district heating scheme (Coldrenick Farm Offices) 5 miles away. The latter has a 130 kW Eta Hack boiler and heats five offices and a farmhouse.

Business Objectives

James Mutton started growing miscanthus as a rhizome producer for Bical in 2003. This contract ceased in 2008 when Bical went out of business. Mr Mutton began exploring the animal bedding market in 2009 and early trials of a basic specification were a success with favourable feedback from local users (keepers of horses, dairy/beef cattle, poultry and pets).

Mr Mutton was one of the first farmers to benefit from funding under the England Rural Development Programme. This provided a 40% grant towards the £400,000 capital costs of a miscanthus processing facility. The facility includes a 1,100 square metre storage shed, dust extraction equipment, bagging plant and briquetting press. A drying floor was added later at a cost of £50,000.

In 2017, the farm was successful in a bid for a £35,000 LEADER grant. This was secured through the

Atlantic and Moor Local Action Group and enabled the farm to add a shredding system into the processing line.

The family business invested in two biomass boilers in 2011 and 2012. These were accredited under the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). In total, the two boilers require around 100 tonnes of miscanthus chip per year.

Business Successes

The business has grown in capacity over the last decade. In 2011, the operation processed around 2,000 tonnes of bedding doubling to 4,000 tonnes in 2022.

Currently the farm produces approximately 600 tonnes of miscanthus per year from their own fields (50 hectares) and buys the rest (3,700 tonnes) from 20 growers.

A key to success was focusing on producing a premium product. Mr Mutton realized the qualities of miscanthus over alternative bedding materials, and the potential to highlight its traceability and sustainability compared to alternatives. This made equine bedding an ideal market.

In 2022, Burlerrow farm produced 170,000 premium grade equine bales. Each bale weighs 19kg and retails [in 2023] for £8-£10 per bale. The quality of miscanthus horse bedding products has been ranked highly alongside other types of premium horse bedding brands in the UK1.

Miscanthus horse bedding is particularly interesting to stables as it has a spongy inner core that absorbs up to three times its own weight in moisture and reduces the smell of urine and faeces. As a result, it doesn’t need to be replaced as often.

A typical horse owner would need to start with 5-7 bales topping up with 1-2 bales a week. This equates to 70-80 bales a year costing around £600-£650.

During the processing of equine bedding 20% of the miscanthus is removed as fines. This can be used to produce briquettes and pellets. In 2022, 800 tonnes was processed in this form (200 tonnes of briquettes and 600 of pellets).

Burlyburn briquettes are sold in 15kg bags for £6.50 each in local garage forecourts and by around 25 of the retailers that also sell bedding. They burn well and have a high calorific value but do have a higher ash content than wood briquettes.

The pellets produced are not fuel pellet grade (due to durability and ash content) and are used mainly for bedding. Users need to break them up and sprinkle with water to create a fluffy bed.

Burlyburn also produce a range of firelighters. These are produced by another supplier and include miscanthus mixed with recycled candle wax. Burlerrow Farm sells around 4,000 boxes per year. Although, the profit margin is minimal, the firelighters promote the briquettes and help with the communication of a positive story involving a circular economy of biobased materials.

Through the management of other growers’ land, Burlerrow Farm have improved the husbandry of the crop and increased yields. New activities include post-harvest management such as sub-soiling every 3-4 years to rejuvenate the rhizomes and deal with compaction, soil analysis every 3-4 years to enable intervention where necessary (e.g. supplements to adjust pH and concentrations of trace elements) and better weed control.

Challenges

The expansion of the Burlybed brand was dealt a blow in 2019 when there was a major fire in the barn and storage area. The facilities were replaced in full, but this caused a great deal of upheaval for the best part of a year.

However, the main issue with increasing production is the limited availability of miscanthus. Burlerrow Farm are looking to source 5,000 tonnes in 2023 but this is proving difficult.

Burlerrow Farm doesn’t have a contract with their growers. Although, the farm would like a greater degree of clarity to shore up supply, the message they get from their growers is that they don’t want to be tied into a long-term deal.

Burlybed are hoping to expand beyond the south of England and Wales into the Midlands (Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire). However, this is not easy as their main competitor (Ethos) is located in the Midlands which means they can achieve much lower haulage costs.

By being very early adopters of biomass boiler technology, the farm is exempt from RHI air quality emission thresholds. This came into force in September 2013 and required boilers to have emissions certificates for particulates and nitrogen oxides. Mr Mutton is one of several growers in the SW using miscanthus in an Eta boiler and has found that it works well with this fuel.

Other growers could follow the Burlerrow Farm example, but they would be required to perform an in-situ emissions test, which is expensive and install additional abatement equipment. As a result, on-farm use of miscanthus in biomass boilers has not been widely replicated.

Cost and benefits

In 2022 Burlerrow Farm were offering growers £74/tonne ex farm for miscanthus bales. This is a competitive price compared to other end markets for miscanthus cane. A farmer achieving a 12 tonne per hectare yield should therefore be able to achieve a net return of ~£400 per hectare per year.

Mr Mutton achieves yields of around 12 tonnes per hectare (@ 15% moisture content) on his own land. The only ongoing cost is chip harvesting each year. This would mean an annualised production cost of around 1.1 pence per kWh when used in his boiler.

On top of this, other costs should be included such as lost income from the land (£200 per year), costs associated with RHI compliance (e.g. Sustainable Fuel Register fees of £200 per year) and additional servicing and parts for the boiler (£300 per year). Even with these costs, the price of self-supply miscanthus is only 2.75p/kWh which is a huge saving on the alternative of purchased woodchip (currently around 4.8p/kWh) or oil / gas (currently over 10p/kWh).

Mr Mutton’s first miscanthus crops will be harvested for the 20th time this year. The yields being achieved do not suggest any falling off in viability and the plantations may last longer than 25 years. So, based on annualized costs of establishment, the miscanthus production price is likely to fall.

In 2020, Mr Mutton entered into a Countryside Stewardship agreement. This includes a wide wildlife margin around the outside of the miscanthus crop. This is worth £250 per hectare of nonplanted area and will help to further increase the farm’s enterprise margins.

Burlerrow Farm currently employs 8 people to process and market the Burlybed, Burlyburn and Burlybale range.

- Miscanthus Crop

- Miscanthus Bales

Lessons Learnt and Recommendations

Mr Mutton and his family have fully embraced the opportunity to develop a business from miscanthus. It has been a huge learning curve, but Mr Mutton has remained open to new ideas and market opportunities. He has also been very adept at gaining funding for these enterprises and as a result has created a thriving business.

The Burlerrow Farm team are always looking to innovate and increase efficiency. For instance, the farm is currently developing a pelleting process where fines (<3mm particles) removed during processing are immediately turned into pellets without unnecessary movement or storage of the powdery material.

This is an efficiency saving but also reduces airborne particles, improving working conditions for his employees.

Efficiency savings are also being made in the miscanthus crop. Mr Mutton is starting to rake leaf and stubble in the crop every 3-4 years. This doesn’t impact on the potential productivity of the crop and increases the harvested biomass by 25% in the years that it is done. This material is suitable for making fuel logs and pellets.

The team are also looking at energy saving operations, with solar PV due to be installed on the roofs of production buildings and a ground mounted system being investigated to increase the business’ self-sufficiency.

1 Choosing the right bedding for you and your horse

Horse and Hound, 31 July 2021

![Figure 6. Planting of SRC willow in a number of HSAs at AFBI Hillsborough Farm[8]](https://www.biomassconnect.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Figure-6-250x300.jpg)